THE EXPERIENCE

Editor’s note: On March 26, 2012, James Cameron made a record-breaking solo dive to the Earth’s deepest point, successfully piloting the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER nearly 7 seven miles (11 kilometers) to the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench. DEEPSEA CHALLENGE is now in its second phase—scientific analysis of the expedition’s findings. Click here for news about the historic dive, an exclusive postdive interview with Cameron, and information about the next phase of the expedition.

Diving to the deepest point in the Mariana Trench is something like riding a cramped elevator that starts in a steamy tropical forest and ends in the dead of night at the North Pole.

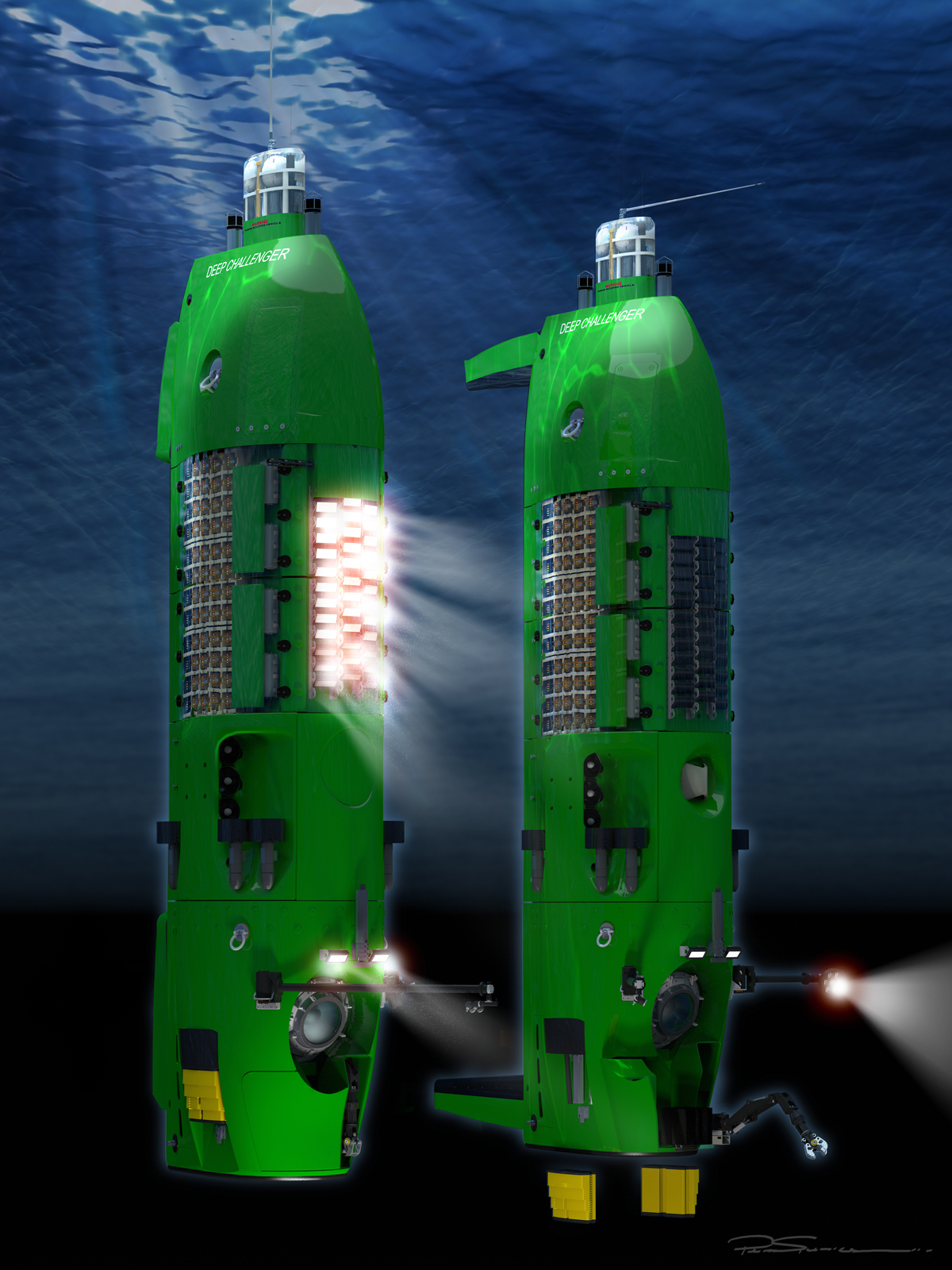

The temperature will drop from sauna-like at the surface to meat-locker cold at the bottom. As the sun’s rays cannot penetrate the ocean’s deepest parts, the water goes from brightly lit to inky black. The sub will take about two hours to reach the seafloor and will have six hours or more to explore the deep-ocean frontier for clues about new life-forms and the forces that shape our planet. On ascent, due to the sub’s unique design, the time from bottom back to the surface will be only an hour, at speeds over 7 knots. James Cameron will pilot several dives during the expedition in the single-person sub, but here’s a snapshot of what the team expects during his journey to the Challenger Deep.

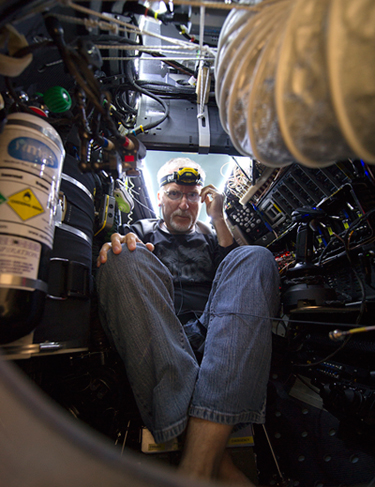

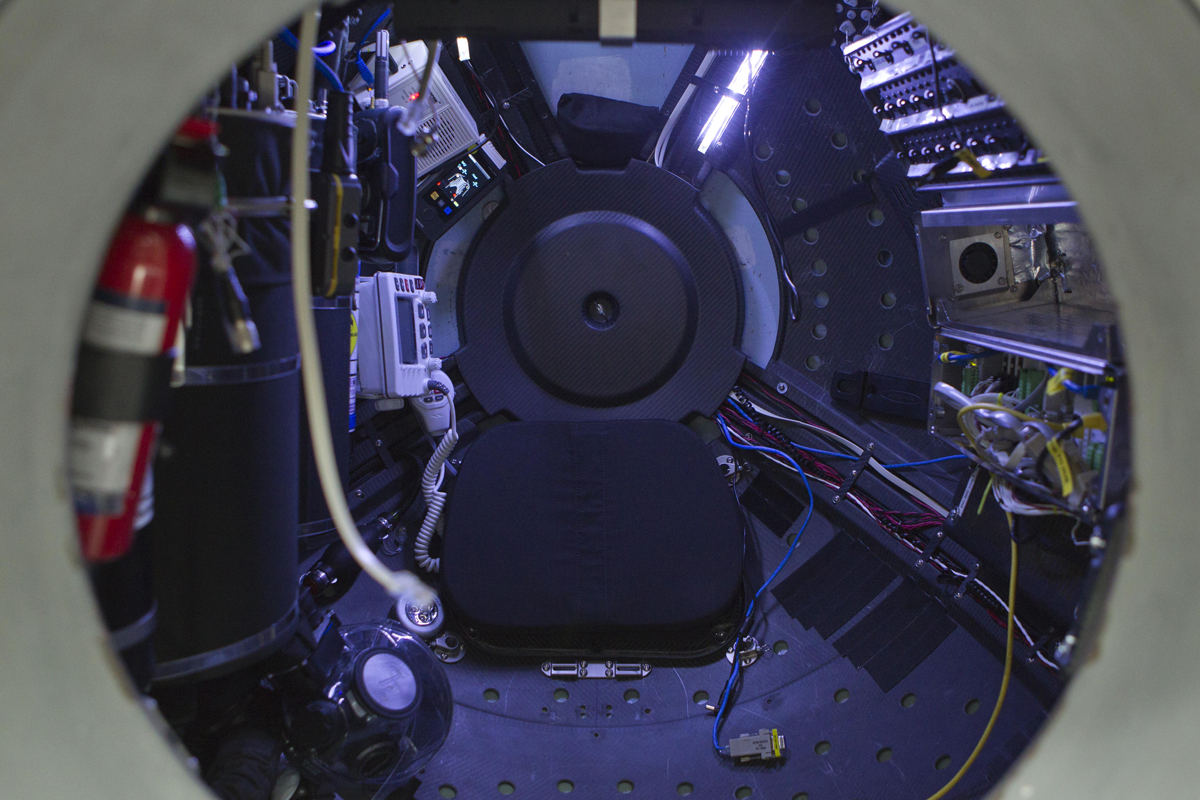

On dive morning, Cameron will wear a breathable T-shirt and the bottom half of a fire-resistant suit. While the sub is still resting in its cradle on the deck of the Mermaid Sapphire, Cameron will enter the pilot sphere through the 18-inch-diameter (46-centimeter-diameter) hatch of the sphere, which has an exterior diameter of 48 inches (122 centimeters). Drawing from months of yoga to maneuver his tall frame—he’s 6’2” (1.9 meters)—inside the densely packed sphere, he’ll get into the pilot’s seat in the launch position. Like an astronaut in a capsule on the launch pad, he’ll be on his back, with his knees bent, as the crew passes him the “port camera” (a Red Epic); joysticks to control the sub’s thrusters, manipulator, and external camera boom; and vacuum-packed, electronically heated clothing. He probably won’t be thinking about cold at this point—the sphere, heated by the internal electronics, will be sweltering.

Then the crew will bolt the sphere’s 430-pound (195-kilogram) hatch shut and prepare to transfer the sub—with Cameron locked inside—from the ship’s deck into the water, a process that engineers consider to be among the most dangerous parts of the dive. To do this, a 23-ton crane will lift the submersible out of its cradle and into the ocean. Once in the water, attached bags of air will rotate the sub into its vertical “dive position” before it begins its descent. “Release, release, release!” Cameron will say, and support divers will pull the quick-releases that jettison the lift bags, beginning his descent. Like a gravity rocket aimed at the center of the Earth, the sub will plummet quickly out of sight and beyond the reach of sunlight.

The sub will descend at about 5 knots, about 500 feet (150 meters) a minute, or the equivalent of a turbulence-prone mini-elevator that travels 40 floors per minute. Along the way, Cameron will monitor key systems, maintain surface communications, and narrate to two small 3-D cameras. He won’t be able to stretch his legs or spread his arms. He’ll be surrounded by oxygen tanks, air scrubber, wires, switches, and screens.

The temperature inside the sub will decrease. The sub’s sensors will send messages to the expedition doctor at the surface with precise data about the sphere’s oxygen, carbon dioxide, and temperature levels so that he can assess the pilot’s well-being. Cameron will communicate with the surface via an acoustic modem that shifts the frequency of his voice and sends out powerful bursts of sound through the water that can be received miles away. But if voice communications get too faint or scrambled, he will switch to text messaging.

At 13,000 feet (3,960 meters), the sub will be in the midst of the abyssal zone, where light no longer penetrates the water and bioluminescent creatures glow in the dark. He’ll still have 23,000 feet (7,010 meters) to go before encountering the seafloor.

When Cameron is about 400 feet (120 meters) from the bottom, information on a screen will tell him the sub has detected the ocean floor. In preparation for “landing,” he might release some steel pellets to lighten the sub and slow down its descent; he might power up his thrusters, check his lights and cameras, and decelerate. When he’s trimmed the sub neutrally buoyant, he’ll thrust gently downward for a soft and controlled landing in the alien landscape 7 miles (11 kilometers) down. A text message will likely rise to the surface: “At bottom.”

Then Cameron will go into explorer mode. He’ll use joysticks to power the 12-ton vehicle, searching for new animal species and imaging rocks that tell the story of the boundary between two tectonic plates—and that could help us better understand the devastating tsunamis that originate in these deep subduction zones. While the six propellers of his horizontal thrusters power him along the seafloor, Cameron will encounter sights no human has seen before. What exactly? Nobody knows—that’s why he’s going.

Normally all would be pitch-black at the bottom, but the sub will illuminate the ocean with an eight-foot (two-meter) panel of LED lights. Cameron will likely be able to see for about 100 feet (30 meters), but clouds of sediment could obscure his view. His eyes will go from his virtual viewport, which gathers wide-field video of the ocean depths, to smaller screens, which display what other cameras are seeing and give him sonar and other data. On his command, a hydraulic manipulator arm will emerge from the bottom of the sub and unfold. The pilot can control the arm with a joystick as its metal claw plucks rocks and/or suctions up small animals from the seafloor and deposits them in a box of samples for the scientists eagerly waiting at the surface on the Mermaid Sapphire.

After up to six hours have gone by—a limit determined by the sub battery life—Cameron will flip a switch and drop more than 1,000 pounds (450 kilograms) of iron ballast weights onto the ocean floor. Freed from the forces of gravity, the lighter-than-water foam beam of the sub will take over. The sub will whirl skyward, starting its ascent fast. To prevent the sub from violent motions, a stabilizer fin—basically a mini-airplane wing—will calm its ascent and the sub will travel along a helical path as it ascends up the water column. Cameron will return through the extreme depths of the hadal zone, then back through the ink-black abyssal zone, and finally rise into the warmer top ocean layer. As the water pressure drops, a flotation bag will automatically emerge from a hatch and fill with nitrogen gas. At about 30 feet (9 meters) below the surface, a strobe light will fire up. Then the sub will pop to the surface like a breaching whale.

It will probably be evening when Cameron surfaces; lights, global positioning, and other location systems will help the two support ships—the Mermaid Sapphire and the Prime RHIB—locate the submersible. Divers will enter the water to attach more float bags to the sub, and the crane will lower to the ocean once again to hoist the sub, with Cameron inside, back into its cradle on the deck. Before the hatch is opened, the team will retrieve the scientific samples to make sure the scientists can work with them as soon as possible. Then crew members will use a davit and hand-winch to open the hatch. Cameron will emerge, undoubtedly a bit stiff, but elated. The dive will be complete.